In flaunting his rudeness and scorn of all refinements, Whitman aroused the class-conscious fears of such genteel critics and literary historians as Barrett Wendell, professor of English at Harvard College and personal friend of the “Boston Brahmins.” In his Literary History of America published in 1901 he could not ignore Whitman, and he gave him equal space with Longfellow and Whittier. But his sympathies were with Lowell, who “lived all his life amid the gentlest academic and social influences of America,” and Whittier, who, though of humble origin, “lived almost all of his life amid guileless influences.” But Walt Whitman, “born of the artisan class in a region close to the most considerable and corrupt centre of population on his native continent,” held a “conception of equality utterly ignoring values,” which Wendell saw as a danger to the American nation. Wendell knew that society was changing, but the increasing political power of the recent immigrants crowding the “New York slums and dingy suburban country” portended a future he could only anticipate with horror: “Those of us who love the past are far from sharing his [Whitman’s] confidence in the future.” But Barrett Wendell was an honest man, and he had to confess that the “substance of Whitman’s poems,—their imagery as distinguished from their form, or their spirit—comes wholly from our native country …. He can make you feel for the moment how even the ferry-boats plying from New York to Brooklyn are fragments of God’s eternities.’ ‘

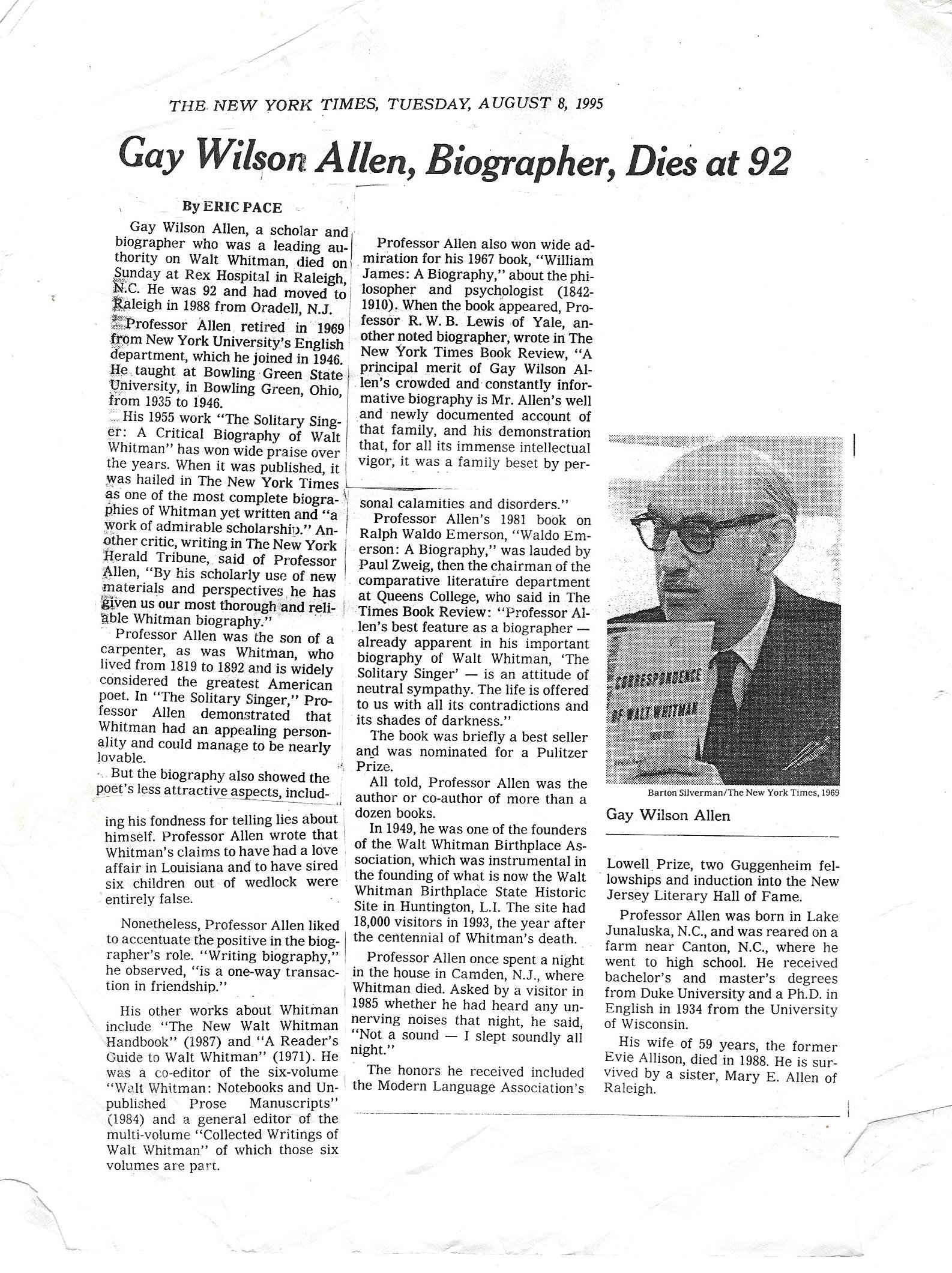

Gay Wilson Allen, A Reader’s Guide to Walt Whitman (Syracuse University Press, 1997)

*****************************************************

Posted here (below), excerpts from Barrett Wendell, A Literary History of America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), pp. 462-479

— Roger W. Smith

March 2023