A Russian scholar wrote to me:

I’m reading Whitman and about Whitman right now. There are very few translations of Whitman into Russian and there is almost no interest in him in Russia now. Can you find an article about Whitman’s importance to American literature and to American culture?

*****************************************************

Whitman himself answers that question.

The largeness of nature or the nation were monstrous without a corresponding largeness and generosity of the spirit of the citizen. Not nature nor swarming states nor streets and steamships nor prosperous business nor farms nor capital nor learning may suffice for the ideal of man . . . nor suffice the poet. No reminiscences may suffice either. A live nation can always cut a deep mark and can have the best authority the cheapest . . . namely from its own soul. This is the sum of the profitable uses of individuals or states and of present action and grandeur and of the subjects of poets.—As if it were necessary to trot back generation after generation to the eastern records! As if the beauty and sacredness of the demonstrable must fall behind that of the mythical! As if men do not make their mark out of any times! As if the opening of the western continent by discovery and what has transpired since in North and South America were less than the small theatre of the antique or the aimless sleepwalking of the middle ages! The pride of the United States leaves the wealth and finesse of the cities and all returns of commerce and agriculture and all the magnitude of geography or shows of exterior victory to enjoy the breed of full-sized men or one full-sized man unconquerable and simple.

The American poets are to enclose old and new for America is the race of races. Of them a bard is to be commensurate with a people. To him the other continents arrive as contributions . . . he gives them reception for their sake and his own sake. His spirit responds to his country’s spirit. . . . he incarnates its geography and natural life and rivers and lakes. Mississippi with annual freshets and changing chutes, Missouri and Columbia and Ohio and Saint Lawrence with the falls and beautiful masculine Hudson, do not embouchure where they spend themselves more than they embouchure into him. The blue breadth over the inland sea of Virginia and Maryland and the sea off Massachusetts and Maine and over Manhattan bay and over Champlain and Erie and over Ontario and Huron and Michigan and Superior, and over the Texan and Mexican and Floridian and Cuban seas and over the seas off California and Oregon, is not tallied by the blue breadth of the waters below more than the breadth of above and below is tallied by him. When the long Atlantic coast stretches longer and the Pacific coast stretches longer he easily stretches with them north or south. He spans between them also from east to west and reflects what is between them. On him rise solid growths that offset the growths of pine and cedar and hemlock and liveoak and locust and chestnut and cypress and hickory and limetree and cottonwood and tuliptree and cactus and wildvine and tamarind and persimmon . . . and tangles as tangled as any canebrake or swamp . . . and forests coated with transparent ice and icicles hanging from the boughs and crackling in the wind . . . and sides and peaks of mountains . . . and pasturage sweet and free as savannah or upland or prairie . . . with flights and songs and screams that answer those of the wildpigeon and highhold and orchard-oriole and coot and surf-duck and redshouldered-hawk and fish-hawk and white-ibis and indian-hen and cat-owl and water-pheasant and qua-bird and pied-sheldrake and blackbird and mockingbird and buzzard and condor and night-heron and eagle. To him the hereditary countenance descends both mother’s and father’s. To him enter the essences of the real things and past and present events—of the enormous diversity of temperature and agriculture and mines—the tribes of red aborigines—the weather-beaten vessels entering new ports or making landings on rocky coasts—the first settlements north or south—the rapid stature and muscle—the haughty defiance of ’76, and the war and peace and formation of the constitution. . . . the union always surrounded by blatherers and always calm and impregnable—the perpetual coming of immigrants—the wharfhem’d cities and superior marine—the unsurveyed interior—the loghouses and clearings and wild animals and hunters and trappers. . . . the free commerce—the fisheries and whaling and gold-digging—the endless gestation of new states—the convening of Congress every December, the members duly coming up from all climates and the uttermost parts . . . the noble character of the young mechanics and of all free American workmen and workwomen . . . the general ardor and friendliness and enterprise—the perfect equality of the female with the male. . . . the large amativeness—the fluid movement of the population—the factories and mercantile life and laborsaving machinery—the Yankee swap—the New-York firemen and the target excursion—the southern plantation life—the character of the northeast and of the northwest and south-west—slavery and the tremulous spreading of hands to protect it, and the stern opposition to it which shall never cease till it ceases or the speaking of tongues and the moving of lips cease. For such the expression of the American poet is to be transcendant and new. It is to be indirect and not direct or descriptive or epic. Its quality goes through these to much more. Let the age and wars of other nations be chanted and their eras and characters be illustrated and that finish the verse. Not so the great psalm of the republic. Here the theme is creative and has vista. Here comes one among the wellbeloved stonecutters and plans with decision and science and sees the solid and beautiful forms of the future where there are now no solid forms.

Of all nations the United States with veins full of poetical stuff most need poets and will doubtless have the greatest and use them the greatest. Their Presidents shall not be their common referee so much as their poets shall.

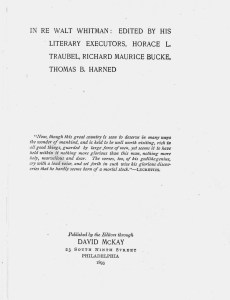

Preface to Leaves of Grass

In the make of the great masters the idea of political liberty is indispensible. Liberty takes the adherence of heroes wherever men and women exist. . . . but never takes any adherence or welcome from the rest more than from poets. They are the voice and exposition of liberty

Preface to Leaves of Grass

America does not repel the past or what it has produced under its forms or amid other politics or the idea of castes or the old religions . . . accepts the lesson with calmness . . . is not so impatient as has been supposed that the slough still sticks to opinions and manners and literature while the life which served its requirements has passed into the new life of the new forms perceives that the corpse is slowly borne from the eating and sleeping rooms of the house . . . perceives that it waits a little while in the door . . . that it was fittest for its days . . . that its action has descended to the stalwart and wellshaped heir who approaches . . . and that he shall be fittest for his days.

Preface to Leaves of Grass

The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. In the history of the earth hitherto the largest and most stirring appear tame and orderly to their ampler largeness and stir. Here at last is something in the doings of man that corresponds with the broadcast doings of the day and night. Here is not merely a nation but a teeming nation of nations. Here is action untied from strings necessarily blind to particulars and details magnificently moving in vast masses.

Preface to Leaves of Grass

the genius of the United States is not best or most in its executives or legislatures, nor in its ambassadors or authors or colleges or churches or parlors, nor even in its newspapers or inventors . . . but always most in the common people. Their manners speech dress friendships—the freshness and candor of their physiognomy—the picturesque looseness of their carriage . . . their deathless attachment to freedom—their aversion to anything indecorous or soft or mean—the practical acknowledgment of the citizens of one state by the citizens of all other states—the fierceness of their roused resentment—their Curiosity and welcome of novelty—their self-esteem and wonderful sympathy—their susceptibility to a slight—the air they have of persons who never knew how it felt to stand in the presence of superiors—the fluency of their speech their delight in music, the sure symptom of manly tenderness and native elegance of soul . . . their good temper and openhandedness— the terrible significance of their elections—the President’s taking off his hat to them not they to him—these too are unrhymed poetry. It awaits the gigantic and generous treatment worthy of it.

Preface to Leaves of Grass

I HEAR America singing, the varied carols I hear, Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe

and strong, The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam, The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off

work, The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deck-

hand singing on the steamboat deck, The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing

as he stands, The wood-cutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown, The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work,

or of the girl sewing or washing, Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else.

See, in my poems immigrants continually coming and landing;

See, in arriere, the wigwam, the trail, the hunter’s hut, the flat-

boat, the maize-leaf, the claim, the rude fence, and the

backwoods village;

See, on the one side the Western Sea, and on the other the Eastern Sea, how they advance and

retreat upon my poems,

as upon their own shores;

See, pastures and forests in my poems—see, animals, wild and

tame—See, beyond the Kanzas, countless herds of buffalo,

feeding on short curly grass;

See, in my poems, cities, solid, vast, inland, with paved streets,

with iron and stone edifices, ceaseless vehicles, and

commerce;

See, the many-cylinder’d steam printing-press—see, the electric

telegraph, stretching across the continent, from the Western Sea

to Manhattan;

See, through Atlantica’s depths, pulses American, Europe

reaching—pulses of Europe, duly return’d,

See, the strong and quick locomotive, as it departs, panting,

blowing the steam-whistle;

See, ploughmen, ploughing farms—See, miners, digging mines—

see, the numberless factories;

See, mechanics, busy at their benches, with tools—see from

among them, superior judges, philosophs, Presidents, emerge,

drest in working dresses;

Walt Whitman,. “Starting from Paumanok”

We suppose it will excite the mirth of many of our readers to be told that a man has arisen, who has deliberately and insultingly ignored all the other, the cultivated classes as they are called, and set himself to write “America’s first distinctive Poem,” on the platform of these same New York Roughs, firemen, the ouvrier class, masons and carpenters, stagedrivers, the Dry Dock boys, and so forth; and that furthermore, he either is not aware of the existence of the polite social models, and the imported literary laws, or else he don’t value them two cents for his purposes.

Walt Whitman, notebook (said of himself)

the perpetual coming of immigrants … the free commerce … the fluid movement of the population

Preface to Leaves of Grass

AUGUST 12, 1863 — I see the president almost every day, as I happen to live where he passes to or from his lodgings out of town. … We have got so that we exchange bows, and very cordial ones.

Walt Whitman, journal entry

Give me such shows! give me the streets of Manhattan!

Give me Broadway, with the soldiers marching—give

me the sound of the trumpets and drums! …

Give me the shores and the wharves heavy-fringed

with the black ships! …

People, endless, streaming, with strong voices, passions,

”Give Me The Splendid Silent Sun” (1865)

NIGHT on the prairies;

The supper is over—the fire on the ground burns

low;

The wearied emigrants sleep, wrapt in their blankets;

I walk by myself—I stand and look at the stars,

which I think now I never realized before.

Leaves of Grass (1867)

Of you, my Land—your rivers, prairies, States—you, mottled

Flag I love,

Your aggregate retain’d entire—Of north, south, east and west,

“A Carol Closing Sixty-Nine.

“the great translator and joiner of the whole is the poet, He has the divine grammar of all tongues, and says indifferently and alike How are you friend? to the President in the midst of his cabinet, and Good day my brother, to Sambo, among the hoes of the sugar field and both understand him and know that his speech is right.—”

Whitman, notebook

A million people—manners free and superb—open voices—

hospitality—the most courageous and friendly young men,

“The mechanics of the city, the masters, well-form’d, beautiful-

faced, looking you straight in the eyes”

“Mannahatta.”

“What would you name as the best inheritance America receives from all the processes and combinations, time out of mind, of the art of man? One bequest there is that subordinates any perfection of politics, erudition, science, metaphysics, inventions, poems, the judiciary, printing, steam-power, mails, architecture, or what not. This is the English language—so long in growing, so sturdy and fluent, so appropriate to our America and the genius of its inhabitants.

Walt Whitman, “America’s Mightiest Inheritance” (Life Illustrated, April 12, 1856)

“Never will I allude to the English Language or tongue without exultation. This is the tongue that spurns laws, as the greatest tongue must. It is the most capacious vital tongue of all—full of ease, definiteness and power—full of sustenance.—An enormous treasure-house, or range of treasure houses, arsenals, granary, chock full with so many contributions from the north and from the south, from Scandinavia, from Greece and Rome—from Spaniards, Italians and the French,—that its own sturdy home-dated Angles-bred words have long been outnumbered by the foreigners whom they lead—which is all good enough, and indeed must be.—America owes immeasurable respect and love to the past, and to many ancestries, for many inheritances—but of all that America has received from the past, from the mothers and fathers of laws, arts, letters, &c., by far the greatest inheritance is the English Language—so long in growing—so fitted.”

Walt Whitman, “An American Primer”

— Roger W. Smith

June 17, 2024